Cruising down Australia’s Great Ocean Road, Matthew Dennison discovers a former whaling town well worth visiting.

The winds that whip the small former whaling station of Port Fairy, where a ribbon of the Moyne River meets the coast of Victoria in south-east Australia, have a crisp, salt tang and, out of season, a decided gustiness.

Some 200 years ago, fishermen plundered the Southern Ocean here for seals and whales to the extent that both were almost wiped out. For much of the 19th century, whale bones littered the long beaches – pale as the surf that creams the craggier reaches of shoreline or the whitewashed whalers’ cottages that recall a vanished world.

This is a town that is a testament to Nature’s power. Its name derives from that of a cutter, Fairy, driven here by a storm in 1827. Its demise as a port was also Nature’s doing: the river silted up, the harbour closed to ships. Its wharf became a mooring place for fishing boats and, today, smaller yachts. On more than one rock above the sea, a plaque records the drowning of a surfer.

Along the Moyne River, Port Fairy.

However, any number of buildings survive from Port Fairy’s heyday, many built of bluestone, a particularly hard basalt of blue-grey widely quarried across Victoria. The result is a townscape in miniature, of remarkable and delightful visual coherence.

Despite tough beginnings, Port Fairy has a settled and charming gentleness. Its lure for visitors – and tourism is key to the town’s economic wellbeing – is a combination of natural setting and the unusual survival of so many colonial-period buildings.

Along the former wharf, a row of handsome, mostly period houses is backed by towering Norfolk pines that scatter their dark cones thickly; wooden jetties and a walkway fringe the riverside gardens. There are boats here year round and the busyness that comes with boats and the percussive clink of serried masts.

Oscars Sitting Room, where the author stayed in Port Fairy.

The town’s main streets march at right angles to the river. Blocks of shops and cafes suggest prettier versions of the streets in vintage Westerns, a clutch of once-municipal buildings is distinctively mid Victorian and the houses stand back from the street behind neat lozenges of well-tended gardens, full of standard roses, agapanthus and shaggy hedges of rosemary. As in seaside towns around the world, these include rentals and second homes. Only a handful have the overtly sterile appearance of houses earning their keep lovelessly.

Several larger buildings hint at Australia’s links with Britain, including the Anglican Church, St John’s, sturdy in its workaday Gothic Revivalism and a dead ringer for churches of similar date in towns across northern England.

At the mouth of the Moyne River, connected to Port Fairy by a causeway, is Griffiths Island. Once the site of a whaling station, it’s been uninhabited since 1954, when the automation of the lighthouse prompted the departure of the island’s last keepers and, two years later, demolition of their cottages.

The enigmatic light house of Port Fairy, situated in one of Victoria’s prettiest towns, looms large against a dramatic sunrise on the water’s edge.

Now a nature reserve, it’s less than a mile long, with rough paths around its perimeter and a sequence of short stretches of beach, both sandy and pebbled. In Australia’s springtime, visitors come to see the nesting colony of mutton birds or short-tailed shearwaters. Black-tailed wallabies, also called swamp wallabies, graze the dense scrubland.

As the island’s only building, the red-and-white lighthouse draws visitors. In truth, the coast of Griffiths Island is more beguiling – the long views across an ocean that stretches without interruption south and ever further southwards.

White-sand East Beach shares these views, but here – the home of Port Fairy Surf Lifesaving Club in unremarkable modern headquarters – the atmosphere is different. This is Port Fairy dressed up as a family holiday resort, the beach a place for play, crested by a row of boxy new holiday houses with big, ugly windows.

The Drift House, Port Fairy

Melbourne families visit annually, often for Easter. Something of the town’s unruffled feeling comes from this sense of continuity: repeat visits from loyal cognoscenti create an atmosphere similar, in a way, to Cornwall’s fishing villages.

This is one explanation for Port Fairy’s surprisingly large number of restaurants. In fact, eating out in so many Australian towns is a revelation. In 2012, a survey named Port Fairy the world’s most liveable small community. Locals in restaurants and cafes, conspicuously relaxed and friendly towards strangers, substantiate this claim.

Oscars, Moyne River.

We spent three days here, breaking the journey from Adelaide to Melbourne. Invigorating sunshine, hearty breakfasts in our hotel – Oscars Waterfront – and tea on the verandah overlooking the marina, wallaby-spotting on Griffiths Island and long walks along the town’s beaches proved wonderfully restorative.

Australians rightly cherish Port Fairy for its survival: few British seaside towns have been so little spoilt. Its charm is distinctive in this stretch of the Australian south. Even the name – apt to raise a smile among cynical British – makes sense on arrival.

While you’re there

- The writer stayed at Oscars Waterfront Boutique Hotel, which offers traditional luxury, Aussie-style. Funkier accommodation, but further from the river, is at the much-lauded Drift House.

- Be sure to book: dinner at Merrijig Inn, old, small, higgledy-piggledy, with a locally sourced menu that changes each day and an excellent wine list

- The town’s quirkiest vibe is found at Coffin Sally, a bar and pizza restaurant in a former coffinmakers’ workshop

Need to know

- Australians eat early, with last orders as early as 8pm

- Bank Street + Co offers Port Fairy’s best flat white – and much more

Cricket, whether at Lord’s or on the village green, is the essence of the English summer — but it needs our help

The World Cup has passed in glory and now the Ashes between England and Australia takes centre stage, but all

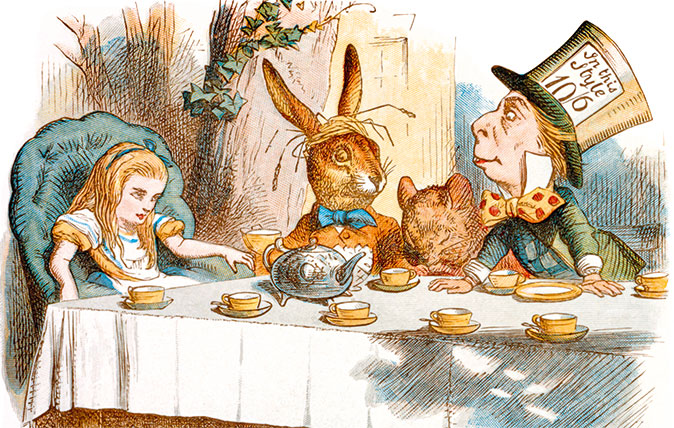

10 of the greatest children’s book illustrators, from EH Shepard to Quentin Blake

Matthew Dennison pays tribute to artists who painted our collective childhoods.

Beagles: The smart little hounds that are both furry friend and working dog

Meghan Markle isn’t alone in her love of these alert, sturdy little dogs with their melting eyes and purposeful demeanour,

Constance Le Prince Maurice, Mauritius: A paradise on the water

Victoria Marston discovers the wonders of Mauritius, complete with bespoke cocktails and famous reef sharks.

St Regis Mauritius: A tropical idyll where the biggest challenge is deciding how to relax next