Children's author Judith Kerr, who passed away this week at the age of 95, spoke to Country Life about her life and career.

Judith Kerr’s much-loved books entertained millions of children across the world. She gave an interview to Country Life at the end of last year, and proved to be just as charming in person as her books suggest. This is the interview, originally published in the magazine on January 23, 2019.

Visitors to Judith Kerr’s house can’t help but exclaim ‘Oh, it’s the kitchen from The Tiger Who Came to Tea’. These Formica worktops from the much-loved picture book will be familiar to the generations who grew up with Sophie and the tiger and Mog the Forgetful Cat, plus her successor, Katinka, now 13 and dozing on a chair upstairs.

Judith Kerr and her late husband, Quatermass author Nigel Kneale, installed the kitchen in their tall Edwardian house in Barnes, south-west London, in 1962, when the area was ‘grotty — no one wanted to live here’. The kitchen was ‘built when they made things to last,’ she adds, rapping the worktop.

Durability is something of which she knows a good deal. Last year, Miss Kerr turned 95, celebrated the 50th anniversary of The Tiger Who Came to Tea and published her 34th book. Her total sales are about 10 million.

Mummy Time, her new book, tells of the fantastical adventures enjoyed by a small boy when his mother is distracted by her mobile phone, a scenario Miss Kerr observes during her daily walks over Barnes Common, started in 2006 after her husband died, because ‘it cheered me up’.

Mummy Time isn’t a criticism of modern parenting, more an observation. Like so many people, Miss Kerr found her own children ‘enchanting and fascinating — and incredibly boring. You take out… well, nowadays it’s a scooter. Then, it was a tricycle, and, after 10 yards, you have to carry it. It is trying.’

Miss Kerr, who had been a BBC scriptwriter, looked after her children herself, ‘but I always kept drawing’. Her first book, Tiger, was honed as a bedtime story for her daughter, Tacy, now a special-effects designer who has worked on the Harry Potter films. Her son, Matthew Kneale, is a writer and historian, who, as his father did, has won the Somerset Maugham Award.

‘Tacy had this terrible thing she used to say,’ Miss Kerr recalls of doing a tedious task such as tidying toys. ‘I’d try to think of something else and Tacy knew and she’d say “Mummy! What you thoughting? Stop thoughting!”.’

Was this the equivalent of sneaking a look at Facebook? ‘Yes, I think it was. Mobile phones hadn’t been invented then, but I think I would have had have one at least some of the time.’

Judith Kerr OBE, photographed at her home in London. ©Clara Molden/Country Life Picture Library

Miss Kerr is working on a new book, ‘sort of in between a picture book and a full-length novel, with lots of drawings’, for 8–9 year olds. She maintains an impressive work ethic, starting after breakfast, when the light is good, and going on ‘as long as you’re sort of getting somewhere’.

At the arrival of our photographer, Miss Kerr dashes up three flights of stairs to tidy her studio, then picks up the interview exactly where we left off. She’s the epitome of a good life, well lived.

It could all have been so very different. Part of the citation for her OBE, in 2012, was for ‘services to Holocaust education’. Her fictionalised memoir of her family’s escape from the Nazis, When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, is essential reading for both German and British children.

Her father, Alfred Kerr, a writer and critic, had his books burned for mocking the Nazis. He fled Berlin for Switzerland in 1933, on a tip-off that his passport was about to be confiscated.

He sent for his family just in time: two days later, Hitler came to power. The family moved to Paris, then to London in 1936. George Bernard Shaw sponsored Mr Kerr’s naturalisation.

Both Miss Kerr and her late brother, Sir Michael Kerr, a High Court judge, felt that ‘our childhood was much better than the childhood we would have had if there’d been no Hitler’. Of course, she didn’t realise how bad things were, because her parents were ‘very protective’ and she ‘loved’ life as a refugee. ‘It was very hard sometimes — it was hard to learn French, but then we were both top in French and I know of other refugee children who did the same. With it goes a huge longing to belong.’

She’s been, she says, ‘very, very lucky’; lucky to have left Germany in time, lucky to find a wonderful, supportive husband, lucky that her first book was picked up immediately and lucky to have experienced the best of people. The Blitz was ‘very frightening, but I never saw anyone seriously hurt. My parents both had German accents, but nobody ever said anything nasty to them.’

How, then, has she felt, witnessing the recent rise — indeed, the tacit tolerance — of anti-semitism? A look of anguish crosses her face. ‘I can’t quite believe it,’ she says, quietly. ‘It’s rather shocking, because he [Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn] appeals to the people who want something done and it’s somebody’s fault.’

Miss Kerr’s feelings about the current state of the world, with tolerance and kindness appearing in short supply, seem far removed from the cheerfulness of her books. Like many of her neighbours, she ‘couldn’t believe’ the result of the EU referendum.

‘Those of us who survived the Second World War have lived through probably the safest and most affluent period in history,’ she thinks, ‘but, because I’m so old, I remember how quickly it can change. I remember the war and how, suddenly, the world was a totally different place. I walk about and look at people, out with their children and walking about and shopping, and I think do they realise how fragile it all is?’

In Pink Rabbit, Judith’s alter ego, Anna, wonders whether she’s having the ‘difficult childhood’ necessary to become successful. Was she aware, then, how formative it would be? ‘I probably made more of it in the book,’ she muses, ‘and so much of it has been luck.’

For her young readers, she has this advice: ‘If there’s something they very much want to do, even if it isn’t financially very sensible, it’s worth hanging on for that, rather than feeling, always, that I might have done that. And I just wish them luck.’

On the records: A few of Judith Kerr’s favourite things

Favourite place in Britain? London: walking along the river from Barnes to Hammersmith

Painting? A Rembrandt self-portrait

Music? Mozart’s Great Mass

Food? Strawberries with yoghurt

Book? Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari

Favourite of your own books? My Henry, about an old lady who imagines herself having all sorts of wild excitements with her late husband in Heaven

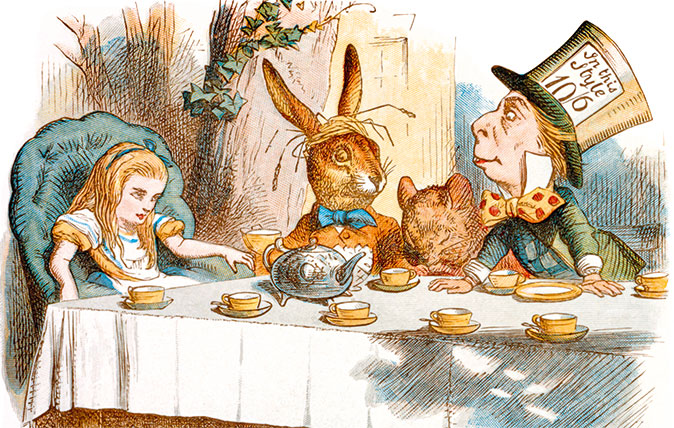

10 of the greatest children’s book illustrators, from EH Shepard to Quentin Blake

Matthew Dennison pays tribute to artists who painted our collective childhoods.

Jason Goodwin: ‘His novels tend to involve a party of opinionated conversationalists descending on a remote country house to talk, drink, dispute and fall in love’

Jason Goodwin tells us about his latest collaboration with graphic designer Richard Adams: a bound and illustrated Christmas story for