Could the Fourth Man be Dioscorides or Apollo and not Shakespeare? Edward Wilson, Emeritus Fellow of Worcester College, Oxford, thinks strong evidence points to the playwright.

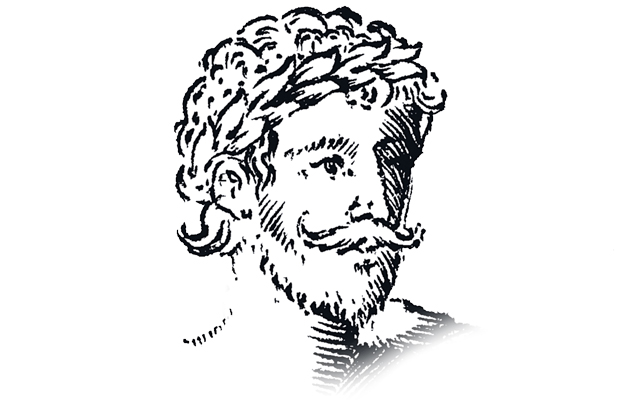

There is now growing acceptance, beginning with no less an authority than Prof Stanley Wells, that three of the men depicted on William Rogers’s 1597 title page of John Gerard’s Herball are real persons as identified by Mark Griffiths in Country Life (May 20)—namely, John Gerard, Lord Burghley and Rembert Dodoens. Debate continues about the identity of the fourth man, whom Griffiths rightly identifies as William Shakespeare, primarily on the basis of the uniquely indicative combination of plants associated with him on the page, the laurel wreath he wears and his dress, which is Roman costume as worn on the Elizabethan stage (see Henry Peacham’s drawing of Titus Andronicus in performance).

Why the Fourth Man isn’t Dioscorides

Early on in this debate, James Wallace objected that this figure is, in fact, Dioscorides, Roman army surgeon and one of the greats of Classical botany. Wallace’s argument was that Dioscorides was depicted in Roman dress on title pages of herbals in this period; for example, he appears on the title page of the second edition of Gerard’s Herball (1633). There seems, however, to be no precedent on the title pages of Renaissance herbals for depicting Dioscorides with a laurel crown.

Nonetheless, Wallace felt that he would be a more likely figure to show on the title page of the 1597 edition than Apollo, an embodiment of the literary arts, and that the laurels worn by the Fourth Man merely signified military honours rather than Apollonian, i.e. poetic achievement. Moreover, Wallace ventured that the novelty of the plants associated with the Fourth Man signified his being a Dioscorides for a new age—a brave assertion in view of Griffiths’s expertise in Renaissance botany.

The image of Apollo

In fact, Griffiths had determined that Apollo is portrayed and named among the figures shown on the title page of Henry Lyte’s A Niewe Herball (1578/9), a work also supported by Burghley, written by an associate of Gerard and based on a text by Dodoens. But the image of Apollo of greatest importance to Griffiths’ research was the one featured on the title page of Neuw Kreuterbuch by Iacobus Theodorus Tabernaemontanus (Frankfurt 1588).

There, Apollo is shown opposite Aesculapius, god of medicine. He wears Roman military dress and a laurel wreath and he holds the poet’s lyre (see image attached). He is there to represent Classical poets such as Ovid and Virgil, whose plant-filled works are freely quoted by Tabernaemontanus (as they were by Dodoens and Gerard) as major authorities. John Gerard used this book and knew its author.

Moreover, a sweet reciprocity ensued whereby elements of Rogers’s 1597 engraving for Gerard were incorporated in the title pages of editions of Neuw Kreuterbuch published after 1598 (chiefly, the goddess Flora and the oval garden).

The Fourth Man must be a new Apollo – and a poet

In short, there is a precise and incontrovertible precedent that establishes the fact that the Fourth Man on Gerard’s 1597 title page represents not Dioscorides, but Apollo and the poets he inspired. Given that the other three figures are portraits of persons alive in the 16th century camouflaged as the characters conventionally shown on botanical title pages, we are looking at a new likeness of an Elizabethan poet.

In her A Portrait of the Author in Sixteenth-Century France (Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1980), Ruth Mortimer reproduces (fig 26, p41) an Apollonian portrait bust of Ronsard wearing a laurel wreath and Roman cuirass and paludamentum (Roman military cape, here correctly depicted rather than the theatrical version worn by Gerard’s Fourth Man) from the 1567 Paris edition of the collected works.

Laurels and classical dress

The portrayal of English authors with laurel leaves and the question of their wearing of classical dress is a topic I have begun to address. The earliest such that I have found so far is the frontispiece to a manuscript presentation copy to Elizabeth of The Tale of Hemetes the Heremyte (1575; British Library MS Royal 18 A.XLVIII, fol. 1r) by George Gascoigne. Here, the poet is shown in modern dress but with a laurel wreath hovering over his head.

The laurel was, in Edmund Spenser’s words, ‘meed of mightie Conquerours/And Poets sage’ (Faerie Queene, 1.1.9). Soon after he published this, the question of which English poet deserved the official laurels became hotly debated – not least because Spenser, widely bruited for the role, blew it by antagonising Lord Burghley first in The Faerie Queene and then, more explicitly, in his verse collection Complaints issued early in 1591 and promptly withdrawn.

It is highly significant that, in the years immediately following this debacle, Shakespeare, by now the most popular poet of the age (see Lukas Erne, Shakespeare and the Book Trade, 2013), was awarded Apollonian bays and dress by William Rogers on the title page of Gerard’s Herball.

Subsequently, Michael Drayton and Ben Jonson would also be portrayed crowned with laurels, albeit wearing their own contemporary clothing – unlike Shakespeare in Rogers’s engraving, they are not Apollo incarnate. Laureate self-presentation was a topic of a number of 16th- and 17th-century poets (see Richard Helgerson, Self-Crowned Laureates; Spenser, Jonson, Milton and the Literary System (Berkeley, etc., 1983)), but, whereas for them the award of laurels was a question of either bold or fretful assertion, Rogers showed Shakespeare, like Ronsard, with both laurels and classical dress, but in a way, as Mark Griffiths has shown, redolent not only of classical statuary but also of the Elizabethan stage.

How Country life revealed the true face of Shakespeare [VIDEO]

Country Life magazine reveals an astonishing new image of William Shakespeare, the first and only known demonstrably authentic portrait of

The true face of Shakespeare: further evidence of its authenticity

Although a Harvard academic claims a 1749 book has proof that Shakespeare’s rebus in The Herball is a printer’s mark,

Why the fourth man can’t be anybody but Shakespeare

A number of commenters have put forward theories of their own. But does the evidence stack up for them? Mark

The true face of Shakespeare: Dioscorides and the Fourth Man

Mark Griffiths explains in depth why the Fourth Man is not Dioscorides.