The saving of Mount Grace Priory in North Yorkshire is a fascinating tale of far-sightedness, persistence and determination. Gavin Stamp tells the story.

Soon after its foundation by William Morris, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) became concerned about the future of the ruins of Mount Grace Priory. The society’s committee may have been alerted to its condition by George Wardle, by Morris himself or by his great friend and collaborator, ‘the best man I have ever known’, the architect Philip Webb.

Both the latter had been working nearby for the industrialist Sir Lowthian Bell at his North Yorkshire seat, Rounton Grange (it is recorded that the austere Webb visited Mount Grace in 1881 and was attracted by the idea of being a Carthusian monk with his own separate room and fireplace).

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

Hearing that the monastery buildings might be offered for sale, it was to Lowthian Bell, ‘as one who knows the ruins area &… appreciates their great value,’ that Hugh Thackeray Turner, Secretary of the SPAB, wrote in 1886.

The committee believed, he told him, ‘that an association of gentlemen of the neighbourhood, making the request from patriotic motives, would be able to obtain the ruins’ and that ‘the buildings ought to be put under the protection of a public body, always open to public criticism’.

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

The house cannibalises the monastic guest range. It was re-ordered by Ambrose Poynter in 1900-01

Bell’s response was swift and positive. He went to see Douglas Brown QC, who owned the 2,500-acre Arncliffe Hall estate of which the monastery ruins formed a small part. The problem was that the estate was heavily mortgaged, so that although ‘Mr Brown entirely agrees with you in the desirability of this portion of the estate being placed in the hands of a body… so as to ensure its preservation… he feels he is powerless in the circumstances in which the Estate is placed’.

Bell added that ‘Mr Brown jun., who has the matter in hand, is a gentleman of refinement and culture, & has promised me to keep my application in view. Personally I feel so much interest in the question that you may rely on my hearty cooperation’.

‘Mr Brown jun.’ was William Brown, the Yorkshire antiquary. It was he who, after his father’s death in 1892, brought in the archaeologist Sir William St John Hope to excavate the priory site and then, in 1898, finally sold the whole estate to Lowthian Bell. The new owner then decided both to repair and conserve the monastic ruins and to restore the old priory guest house, rebuilt as a private residence in the 17th century, as another family home.

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

The obvious choice of architect for this work would have been Webb, with whom he had worked closely on so many projects. Webb, as much as Morris, had been responsible for the ‘Anti-Scrape’ principles of the SPAB and, earlier, he had written to Bell: ‘It is but little understood among architects how serious a matter it is merely to repair and sustain an ancient building, which is often just in a state of equilibrium in many of its parts, and requiring attentive watching as each stone is lifted, or additional weight laid on.’

Unfortunately, Webb had by then decided to retire from practice. And when Bell asked his further advice, offering him the use of Ingleby Hall – ‘a very nice house… I implore you to come down, stay there as long as you choose… I still feel I am in your debt’ – Webb politely declined to be lured back north.

For the care of the ruins, therefore, Bell then turned to a disciple of Webb’s, Alfred Powell, one of the earnest young men working with the SPAB whom Michael Drury has called ‘Wandering Architects’ in his study of that name. Powell worked at both Mount Grace and at Rievaulx Abbey (whose condition was also of great concern to the SPAB), but he was not well, suffering from pleurisy, and, by September 1900, he was on board a P&O cruise ship in an attempt to recover his health.

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

For the work on the house, however, Bell had commissioned the architect and calligrapher, Ambrose Macdonald Poynter. This may seem a surprising choice. The obscure Poynter, whose principal work was the 250ft-high British Memorial Clock Tower in Buenos Aires (since 1982, the Torre Monumental), was an old Etonian who, in 1919, inherited a baronetcy from his artist father, Sir Edward Poynter, PRA (confusingly, himself the son of an architect called Ambrose Poynter).

Poynter had connections with the SPAB circle: he had been articled to George Aitch-ison, the architect of Leighton House, who was on the committee, and he later worked with another of Webb’s disciples, Powell’s friend Detmar Blow.

However, the clue to his employment perhaps lies in his middle name, as Poynter’s mother was one of the celebrated Macdonald sisters, who made interesting marriages, resulting in his having as first cousins Sir Philip Burne-Jones, the son of the artist, Rudyard Kipling and the future Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin.

At Mount Grace, Poynter carried on looking after the ruins and, in 1901–05, he reconstructed one of the monk’s cells (Cell 8, subsequently refitted by English Heritage), an exercise in ‘restoration’ not exactly in accord with ‘Anti-Scrape’ principles.

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

The ruins of the monastery, dominated by the tower of the church, were cleared and repaired from 1896 onwards.

Indeed, Powell wrote to Webb that he was ‘in distress’ about what Poynter – who had appointed a workmen as resident architect – was doing.

In 1902, Webb wrote that he suspected that Poynter ‘was not up to the craft. Ill furnished in the way of study or experience when on real building work. What a mess they have made of “Mount Grace” since Powell had to leave’.

Later, for Lowthian Bell’s son and heir, Hugh, Poynter designed the village hall in Ingleby Arncliffe. He also restored and altered Arncliffe Hall itself, a Georgian mansion by Carr of York, after a fire in 1912. His principal work, however, was to make the former Mount Grace guest house into a home for the Bell family. The building was then described as being ‘in a bad state of decay and was hardly more than a farmhouse, inhabited by a caretaker whose cows grazed in the inner courtyard of the priory’.

Survey drawings, dated 1899–1900, are signed by Ambrose M. Poynter and Pieter Rodeck. Poynter repaired the structure, exposing ancient features such as the inglenook fireplace in the old kitchen (today, the shop). At the rear, he added another projecting wing containing a library.

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

Bell’s principal additions were to the rear of the house, viewed here from the ruins.

At the front, he opened an additional window on the first floor: if it were not for the monogram on the lintel – ‘IBL 1901’ – this would be indistinguishable from the original 17th-century windows (Webb would surely have made sure there was a distinction between new and old work). A fine garden with a pool falls away beneath the house.

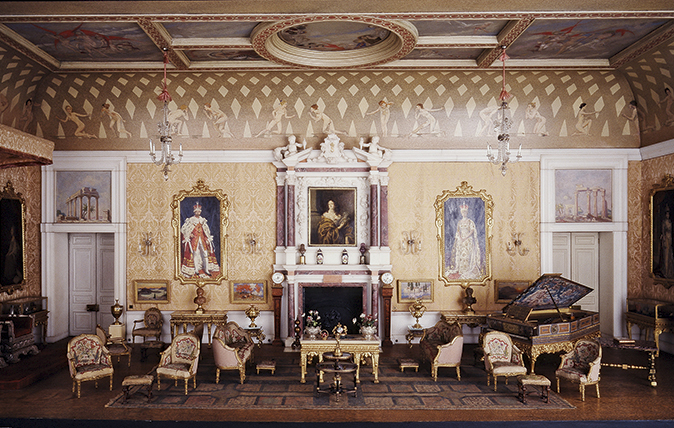

Inside, the rooms Poynter refitted have a modest Arts-and-Crafts character, which may well owe something to Webb. Tile-flanked new fireplaces were inserted within 17th-century surrounds and in the central hall, the walls were lined with salvaged old panellingThese fine rooms were recently restored by English Heritage and a magnificent Morris carpet from another Bell house, Red Barns at Redcar (again by Webb), now enhances the drawing room.

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

The drawing room with its reprinted wallpaper. The Morris carpet was made in 1881 for Bell’s home in Redcar.

With the house made both habitable again and comfortable, Mount Grace became first a weekend retreat for the Bells, used for entertaining and for shooting parties by Sir Hugh and by his son Maurice, the 3rd Baronet, and then, in the 1930s, the family’s main residence. Archaeological work on the ruins continued: in 1915, the SPAB was pleased to report that this work, ‘which has been entrusted to a member of the Society, is being carried out at intervals in order not to interfere too much with the appearance of the ruins’.

In 1927, the priory became the backdrop to the Pageant of Mount Grace, written and organised by Hugh Bell’s second wife, the author and playwright Florence Bell (sometimes known as Dame Eleanore Bell), which told the story of the monastery in words, action, dance and music, with the participants – including acrobats and court jesters – in medieval dress. Inspired by the historical romanticism of the Arts-and-Crafts movement and informed by Cecil Sharp’s research into folk song, this extraordinary event took place over three days, attracted much local attention and was recorded on film.

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

The main hall, fitted with its fire grate and panelling in 1900-1, has recently been refurnished with Arts and Crafts furniture

The pageant was directed by Edith Craig (sister of Edward Gordon Craig and the daughter of the actress Ellen Terry), who recalled a meeting with Lady Bell in the ruins in moonlight in 1925 when she announced: ‘We are going to do a pageant, and we shall have once more the Carthusians living other again in the Cloister of the monastery.’

The restoration of Mount Grace was the last architectural venture carried out by the great ironmaster, metallurgist and politician, Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell, Bt (1816–1904). Born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and made a Baronet in 1885, he and his son Hugh were impressive patrons of the Arts and architecture in Yorkshire, responsible for buildings residential, social and commercial and almost all designed by Philip Webb, who became a friend as well as a trusted architect.

Webb’s principal work for his patron was Rounton Grange, some five miles to the north built in 1873–76 and contained richly decorative interiors executed by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. Sadly, this great house, one of Webb’s finest, no longer stands. During the Depression, the old heavy industries like Bell’s went into decline and the family’s fortunes were further reduced by death duties. In 1932 Rounton Grange was closed. During the Second World War, it became a home first for evacuees and then for Italian prisoners of war before being demolished in 1953.

©Paul Highnam/Country Life

After the war, the future of Mount Grace also became problematic. The Bell family moved to nearby Arncliffe Hall and there was a rumour that Mount Grace might again be a Carthusian monastery. In 1950, guardianship with the Ministry of Works was investigated. The last tenant of Mount Grace, Kathleen Cooper-Abbs, became alarmed as, with characteristic archaeological pedantry, the Ministry not only wished to separate the house from the ruins by a high fence, turning it into ‘a prison’, but also to demolish the wing added in 1901 and even that built in about 1654.

In the event, happily, the 4th Baronet, Hugh, made sure that Mount Grace went to the National Trust in lieu of death duties and, today, the site is administered by English Heritage.

In 1904, Bell was laid to rest under the great tombstone in East Rounton churchyard that Webb had designed back in 1887 after the death of Bell’s wife, Margaret. Webb had designed a number of smaller buildings for Bell in and around the village of East Rounton near Rounton Grange: a coach house, a school, cottages and farm buildings.

The little church itself, dedicated to St Lawrence, was largely rebuilt by the Newcastle architect R. J. Johnson. The three-light east window was filled with new glass by Sir Hugh Bell, the 2nd Baronet, in 1906 as a memorial to his parents. This was designed by the Scottish stained-glass artist Douglas Strachan and, in this magnificent work, St Margaret and St Nicholas flank the figure of St Lawrence, over whose head rises Our Lady of Mount Grace – presumably an allusion to the medieval Lady Chapel which then stood as a ruin on the hill high above the remarkable Carthusian foundation that Sir Lowthian Bell had helped save for posterity.

Mount Grace Priory, North Yorkshire: Cloistered from the world

This magnificently preserved charterhouse offers a compelling insight into late-medieval English monasticism.

Our love affair with Georgian architecture

Gavin Stamp delves into the story behind our love affair with Georgian architecture

A doll’s house fit for a queen: How Lutyens created a Lilliput for Queen Mary

A miniature palace designed by Lutyens and promoted by Country Life offers a fascinating perspective on the 1920s, as Gavin

Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson: Glasgow’s visionary architect

As we celebrate the bicentenary of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, Gavin Stamp considers the remarkable way in which he adapted principles